A. Paul and Rhetoric

Contents

1. Prevalence of Rhetoric

The Greeks and Hellenism generally were rather obsessed with rhetoric. It was considered pivotal to any education.

2. Judicial Rhetoric

Paul’s defense between Felix shows acquaintance with and skill in the art of judicial rhetoric: exordium (introduction), narratio (statement of facts), confirmatio (establishment of facts), refutatio (refutation) and peroratio (conclusion). He stood against Tertullus, “a certain orator,” whom Paul’s accusers used.

3. Renunciation for Preaching

1 Cor. 1:17 tells us that Paul renounced the wisdom or rhetoric because of its danger of emptying the preaching of the cross. The sophist cannot bring people to the knowledge of God (1 Cor. 1:19-20; 1 Cor. 1:31). The fact that he renounced rhetoric, means that he knew it, and could have used it, but chose not to. The sophists used ethos, acting out a character, pathos, manipulating an audience’s feeling, and demonstration, arguments. By contrast, Paul comes in weakness, fear, and much trembling (1 Cor. 2:3) – the absolute antithesis. This weakness, however, showed that the power of the gospel was not human wisdom, but the power of God (1 Cor. 2:5).

4. Use in Letter Writing and Subordinate Way

Certain principles of rhetoric are basic to communication. Things such as “introduction,” “body,” “conclusion,” “arguments,” etc., are universal and Paul also uses these. The three main rhetorical genres in classical Greek were forensic (defends or accuses), deliberative (exhorts or dissuades), and epideictic (affirms through praise or blame). Forensic: Is it just? Deliberative: Is it expedient? Epideictic: Is it praiseworthy? Some have opined that Galatians is forensic. Others deliberative. Etc. Though Paul used conventional forms, he did not rely on them for their supposed effect. And he set them aside, often, that God’s power would be evident.

B. Medium of the Epistle for Revelation

In the Old Testament (representatives of) the tribes of Israel could gather under the hearing of Moses, or Joshua, etc. Prophets spoke often in gathering places, or before kings, and Levites could instruct the people in the laws. In the New Testament, the breadth of missions made epistles more suited. How is this theological significant?

1. Missionary thrust of the NT

2. Personal character of the NT

3. Transformative effect of the NT (2 Cor. 3:1-3).

C. Mechanics of Correspondence

It seems that typically Paul dictated his epistles to a scribe, writing the concluding words himself. Tertius, the scribe who received the dictation of Romans, even added a greeting of his own (Rom. 16:22). Apparently, his concluding words would limit the possibility that someone would forge a letter in his name. Usually, Paul prepared his epistles to be read aloud in the congregations (1 Thess. 5:27; Col. 4:16). Paul was able to use the private couriers who traveled the network of Roman roads or used the advanced means of ship faring to convey letters. If possible, Paul used one of his helpers as courier (Gal. 4:17-18; Eph. 6:21-22; Phil. 2:25-28).

D. Epistolary Forms

1. Chief Characteristics

2. Openings

-Sender: 1 Thess. 1:1a

-Addressee: 1 Thess. 1:1b

-Salutation: 1 Thess. 1:1c

-Thankgiving/Prayer: 1 Thess. 1:2-5;

Note: Galatians and Titus omit this

3. Closings

-Personal details: Rom. 15:22-29

-Prayer requests: Rom. 15:30-32

-Prayer: Rom. 15:33

-Commendation of fellow workers: Rom. 16:1-2

-Greetings: Rom. 16:3-16

-Final instructions and exhortation: Rom. 16:17-20a

-Autographed greeting: 1 Cor. 16:21

-Benediction: Rom. 16:20b

E. Other Forms

1. Formulae “I would not have you ignorant” (1 Thess. 2:1)

2. The Diatribe anticipative objection: Rom. 3:1; Rom. 6:1

3. Liturgical Elements

a. Creedal Confessions

b. Hymns hymnic and confessional material (Phil. 2:6-11; 1 Tim 3:16)

c. Doxologies

d. Benedictions

e. Prayer Acclamations

(i) Amen

(ii) Abba

(iii) Maranatha

F. The Canon of Pauline Writings

1. The Number

13 books bear the name of the apostle Paul. Hebrews has often been ascribed to Paul (see also Belgic Confession of Faith). That would make 14. Since Hebrews has its own character and specific subject matter, and its inclusion in this course would overload it, we reserve its treatment for another course. We know that Paul also wrote other epistles. 1 Corinthians 5:9 refers to an epistle which is no longer extant. Col. 4:16 refers to a letter that was sent to Laodicea. Undoubtedly Paul had an extensive correspondence. His lengthy imprisonments allowed him the time to compose letters to the various churches.

2. Collection

Our present collection of letters is organized from the longest to the shortest (Romans to Philemon). Thus its order is not chronological. The fact that some of his letters were aimed to circulate among the churches might have led to someone collecting all the available letters. Perhaps Timothy or one of the other associates of Paul were responsible for this. 2 Peter 3:16 suggests that the collection of Paul’s epistles were already available even for other apostles to read, and were early on already being recognized as Scripture.

3. Classification

a. Eschatological: Thessalonians

b. Soteriological: Galatians, Corinthians, Romans

c. Christological / Ecclesiology: Ephesians, Colossians, Philippians, Philemon

d. Pastoral: Timothy and Titus

G. Opening and Closing of Galatians

1. Opening: Galatians 1:1-2

a. under identification of sender – the source of apostleship expanded: “not from men nor through any man but through Jesus Christ and [from] God the Father, who raised him from the dead.”

authority not grounded in human authority

double positive references: from Christ and Father

b. co-senders: only letter where Paul includes all believers as co-senders

Paul claims support of all who recognize apostolic status

2. Rebuke: Galatians 1:3-10

Thanksgiving Omitted (compare 2 Cor. / the Pastorals)

The situation is so acute that thankfulness is not in order, for there has been a radical departure from the gospel

3. Closing: Gal. 6:11-18 “a hermeneutical key, unlocking the primary intentions of Paul that are at work in this important, yet rather complex, letter” (93).

Gal. 6:12-15: Contrast between Judaizers and Paul

Gal. 6:12-13: The Judaizers

Gal. 6:12a: Their action denoted: constraint to circumcision

Gal. 6:12b: Their true motives pronounced:

carnal show

avoid persecution

Gal. 6:13: Their true motives explained:

do not keep law

glory in flesh

Gal. 6:14-15: Paul

Gal. 6:14: His action denoted: glories not in flesh but in cross

Gal. 6:14b: His motives pronounced: crucifixion of/to world

15: His motive explained: new creature avails

In this unique closing of the letter to the Galatians, Paul reiterates and climaxes his themes, showing the stark contrast between the “gospel” of the Judaizers and the gospel of Christ, their respective heralds (Judaizers and Paul), and motives. The former is a “gospel” of flesh and show; the latter a gospel of Christ and in him a new creature – true cause of glorying.

The Cross – Paul’s Glory

Paul will fix his boast / glory and esteem upon nothing other than the cross

This orientation:

1. Sets the Flesh and World in Proper Light

2. Sets Christ and New Creature in Full Light

H. Diagramming and Tracing the Argument

Any exegesis that does not take the argument of the passage into consideration will fall short of mining precisely and fully the meaning of the text. Two important tools to that end are diagramming and tracing the argument.

Diagramming

Diagramming is a linguistic tool in any language that arranges sentences in such a way that shows the logical relationship between the parts. Essentially, diagramming sentences is a careful reading of the text, which is always imperative for exegesis.

Philippians 3:14

Explanation: Leaving aside the context for a moment (which is actually quite important, since verse 14 continues the sentence begun in verse 13; nevertheless, for time’s sake), note from this diagram that the heart of the sentence is Paul’s pressing forward. This central verb is flanked by two prepositional phrases. The first concerns the goal towards which Paul is pressing; the second concerns the prize he has in view at the goal. It is on this “prize” that Paul focuses, modifying it with a number of words as an “upward calling” (or “heavenward call”) from God in which Christ functions in a central fashion. The word “call” is something that unites the beginning of the Christian life with the end. Paul was first called and set running this race through the call. When he finishes the race, he will be gathered to Christ, who is now above. He is picturing it as follows: God is constantly calling Paul’s attention upward at what awaits him. In a certain sense, both prepositional phrases denote the same thing – the terminus of the Christian life. The first term, “goal,” however, stands more obliquely in the future; the “prize,” however, receives a theocentric, christocentric, and soteriological character that shows Paul’s “pressing forward as a runner” in remarkable light. Paul is enveloped and energized by a heavenly calling in Christ from God. This so takes hold of him and draws him as a vacuum to that which can fill it.

C. Tracing the Argument

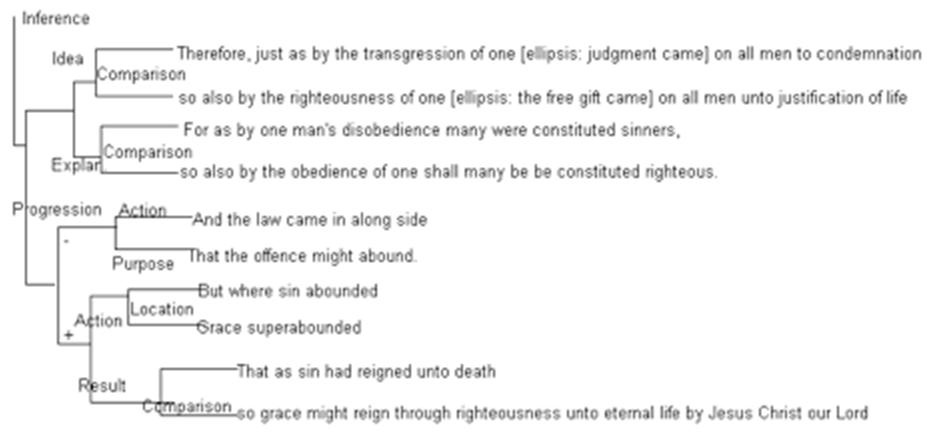

It is possible with diagramming alone to become too focused on the “trees” as opposed to the whole “forest.” To avoid that, it is helpful, especially for complex passages, to trace the argument at a more syntactical level. The connecting words (conjunctions) then become extremely important. See the following analysis of Romans 5:18-21

Explanation: In the context Paul has been setting for the great doctrine of federal headship in both the scheme of condemnation (Adam) and justification (Christ). He had begun with his positive assertion in vv. 12. Then he had moved to set forth the parallel between Adam and Christ in terms of the dissimilarity (vv. 15-17). Now in vv. 18-19, Paul resumes what he had begun by asserting and explaining the similarity between Adam and Christ. What he had treated in verse 15-17 negatively, nevertheless so obviously set forth the connection, that he can begin with an inferential particle (“therefore”).

In verses 20-21, Paul progresses in his argument by showing what the entering in of the law accomplished within this scheme. It takes the side of sin in the sense that it makes sin “abound” (v. 20a). Grace, on the other hand, mysteriously super-abounds in that very place (v, 21) with the result that as sin had reigned, so grace reigns even more abundantly through Jesus Christ.